The Chemistry of Petrichor: Why Rain Smells So Good

How summer heat, soil bacteria, and storms create the unforgettable smell of rain

This article is part of a series on the chemistry of aromas and how they connect to memory. If you’re curious about another familiar scent, check out my earlier piece: Why the Smell of Cut Grass Reminds People of Summer (free link)

A Typical Summer Afternoon…

You can feel the blazing Sun overhead, transforming the air into a smothering blanket. The nearby pavement sizzles in the heat, and you half imagine it could fry an egg within seconds. Looking down at the grass, you can see summer’s toll on the blades. Some are losing color. Others are dead. The cicadas buzz furiously. Beads of sweat form quickly on your forehead and arms. The humidity makes it difficult to be outside for too long. It’s a typical July afternoon, one that seems like it will never change. Until it does.

Clouds gather quickly on the horizon, swallowing the once brilliant sunlight. For a moment, the air seems to hold its breath. The buzzing cicadas become quieter. Thunder rumbles far away. The wind shifts. It’s now cooler and carries bits of dust.

Suddenly, you feel something hit your skin. First, it is just a drop or two, but the pace slowly increases. You look down and watch the raindrops splatter on the dirt and pavement. The dry ground thirstily sucks in the tiny amount of water. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, your nose catches a new scent - something strong, earthy, clean, and even “electric.” It seems to envelop you — the smell of rain.

You have smelled it before. But what exactly are you smelling? How can simple raindrops smell so powerful? And why does the summer heat seem to intensify it?

The answer lies in chemistry. Let’s break it down!

What’s That Smell?

That distinctive, earthy smell that hits your nose after a light rain is known as petrichor. It was coined in 1964 by Isabel Joy Bear and Richard Grenfell Thomas from the ancient Greek words for rock/stone (πέτρα) and divine blood (ἰχώρ), loosely translating into English as “rock essence.” [1] To many people, petrichor smells earthy, musky, yet also fresh, clean, and wet. Ask anyone how they feel upon smelling it, and you will hear many say that it makes them feel calm, happy, and even energized. For some, petrichor is intricately linked to memories of summer. One whiff brings nostalgic memories of summer days long past and thoughts of rainy days and childhood.

Petrichor is not the smell of rainwater, though. Instead, it is a blend of different components found in the soil or on surfaces that together make a unique aroma. Rainwater is merely the delivery vessel for this mixture. There are three major components of petrichor, along with a fourth one whose presence depends on the weather[2]:

Plant oils - secretions of plants and their breakdown products that are more common during dry periods.

Geosmin - an alcohol created by certain bacteria in the soil that is primarily responsible for the earthiness notes of petrichor.

Aerosols - tiny particles of solid or liquid suspended in the air.

Ozone (sometimes) - a form of elemental oxygen that is produced when lightning splits oxygen molecules (O₂) in the air.

When put together, these components create the scent that we notice after it rains. The exact composition and overall aroma vary depending on the local plants, the soil, and the weather.

How Plants Help Create the Scent of Rain

The production of petrichor begins with plants and the protective compounds they release into the environment. During periods of dry weather, plants produce various organic compounds known as volatile plant oils (VPOs).[3] These oils accumulate on and around the plants as the dry weather persists. Thousands of VPOs are known to exist, but the most common compounds are fatty acids, terpenes, and terpenoids.

Fatty Acids - the building blocks of fats, lipids, and oils.

Terpenes - the hydrocarbon building blocks of many essential oils produced in plants.

Terpenoids - Derivatives of terpenes used for plant defense, coloration, scent, and flavor. They often contain oxygen atoms and are common in aromatic plants.

Plants produce these compounds to help conserve water during periods of dry weather. By secreting VPOs onto their leaves, stems, and the surrounding soil, plants reduce or eliminate the excess loss of water. VPOs may also prevent seeds from germinating in the soil during drought and provide a defense against disease or herbivores.[4]

Geosmin: the Source of All That Earthiness

Another major component of petrichor is geosmin, an organic molecule produced in soil by certain species of bacteria such as Actinobacteria and Cyanobacteria.[5] If you have ever smelled a freshly tilled garden, you have smelled geosmin before! Outside of the soil, geosmin is also produced in fresh surface water by certain algae. In cases of high die-off, significant amounts of geosmin can be released into the water, making it rather unpleasant to drink for some people. The molecule is also primarily responsible for the earthy taste of beetroots.[6]

Humans are extremely sensitive to the smell of geosmin, being able to detect it at concentrations as low as 0.4 parts per billion (ppb) or even lower![7] Put another way, humans can smell less than 1 microgram (μg) of geosmin per liter of air or water. This extreme sensitivity is likely no accident, as some biologists have speculated that it evolved to help human ancestors locate suitable drinking water.[8] Other living things are sensitive to geosmin, as well. For example, some species of ocean fish use geosmin to migrate from the ocean into estuaries and rivers.[9] Geosmin is also partly responsible for the smell and taste of freshwater fish.

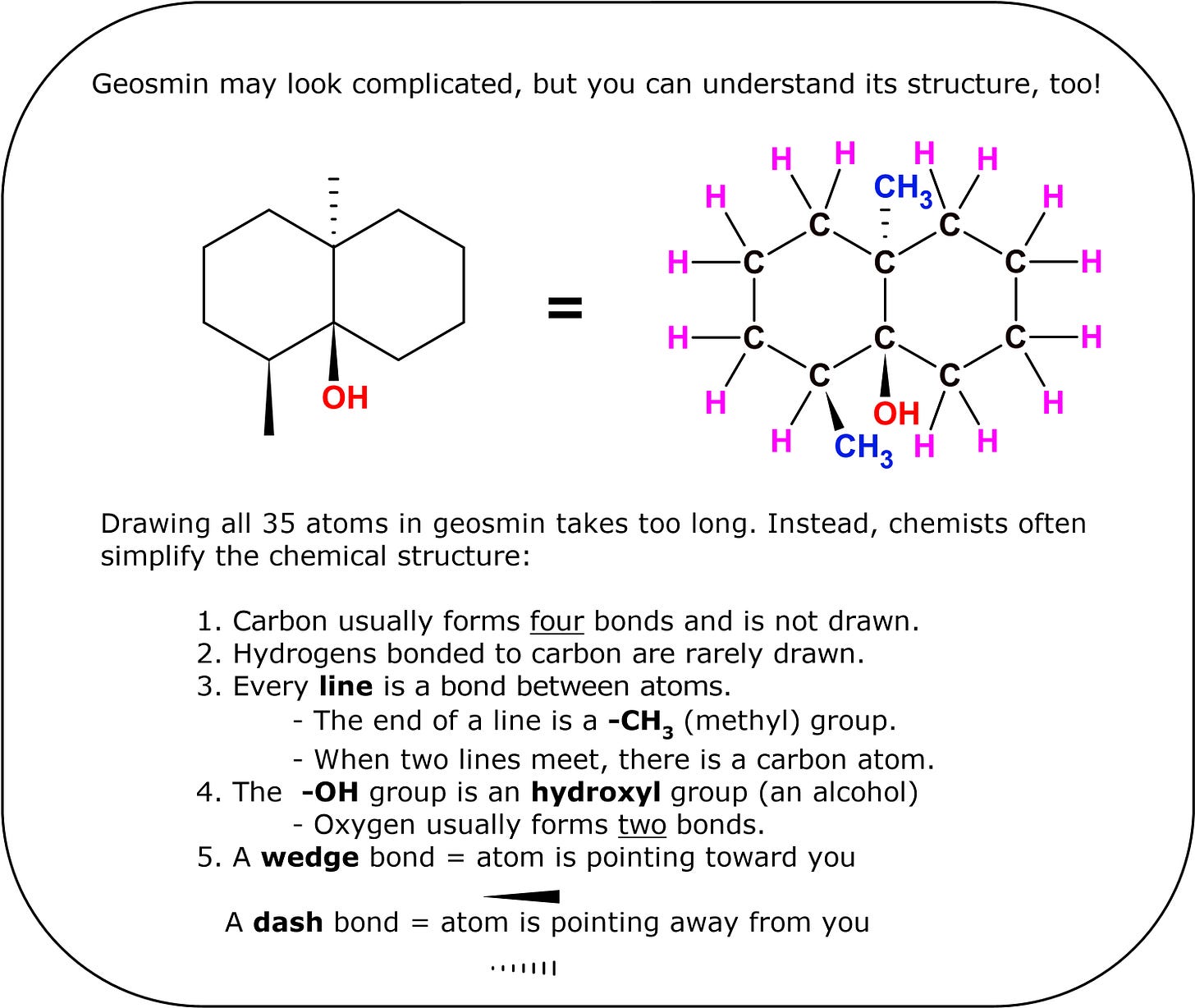

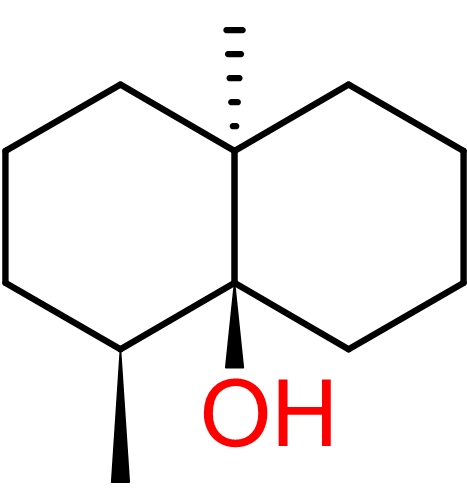

Chemically speaking, geosmin is an alcohol because it contains an -OH (hydroxyl) group. The backbone of the molecule consists of two rings fused together. Geosmin is completely nontoxic to humans and decomposes in the presence of acid. Cooks take advantage of this when they add citrus juice or vinegar to freshwater fish. The low pH of these solutions helps break down some or all of the geosmin present in the fish.

But how do geosmin and the compounds mentioned earlier reach your nose? That’s where the rain comes in.

How Raindrops Release Petrichor Into the Air

Petrichor is often released into the air when raindrops hit something like soil, asphalt, or stone pavement.[10] The water rushes into small pores, trapping air in tiny bubbles that rise to the surface. There, these bubbles quickly pop and release aerosols and chemicals that were once just sitting on the surface, undisturbed. This is where that distinctive smell comes from, just after the rain starts falling. Certain soil types, such as clay and sand, are known to produce a stronger smell.[5]

Slower raindrops produce more aerosols, and people are more likely to notice petrichor after light or moderate rain. In heavy rains or downpours, the components of petrichor do not have as much of a chance to rise into the air. Instead, they remain trapped in the water on the ground or are even washed away.

Why Summer Rain Smells Stronger

Many people often associate the smell of petrichor with the summer season, and there is a good reason for that. In fact, it is directly related to why the smell of grass is also linked to summer![11] As discussed earlier, plants tend to release more volatile organic oils during the intense heat of summer. The high temperature and intense sunlight, however, make it easier for these compounds to react and produce new compounds such as aldehydes, ketones, and organic acids. Many VOPs will break down into simpler molecules over time. These breakdown products can have their own unique aromas. The exact composition and aroma contributions depend on the varieties of plants growing locally.[12]

The summer heat also increases the production of geosmin by soil bacteria, especially when the soil was previously wet. This geosmin accumulates on the surface until something like raindrops releases it into the air. During the colder months of the year, geosmin production is lower or even nonexistent.

Ozone: The Sharp Smell of a Thunderstorm

One component that is not always associated with petrichor is ozone (O₃). Ozone is a reactive form of elemental oxygen that usually exists on Earth high up in the atmosphere (the famous Ozone Layer).[13] There, it absorbs ultraviolet radiation from the Sun, which protects living things on the surface. Ozone, however, can be produced closer to where we live.

Summer thunderstorms can often be a source of ozone close to the surface. The atmosphere contains approximately 20% oxygen in the form of O₂ molecules. These molecules can be split by lightning, forming individual oxygen atoms that are highly reactive. These oxygen atoms then react with other O₂ molecules to form ozone molecules. Although not everyone is sensitive to the smell of ozone, many describe it as clean, electric, and even metallic.[13] This is why some people claim to “smell lightning” during a storm. You can also smell ozone away from a thunderstorm, as it is often carried off on strong downdrafts.

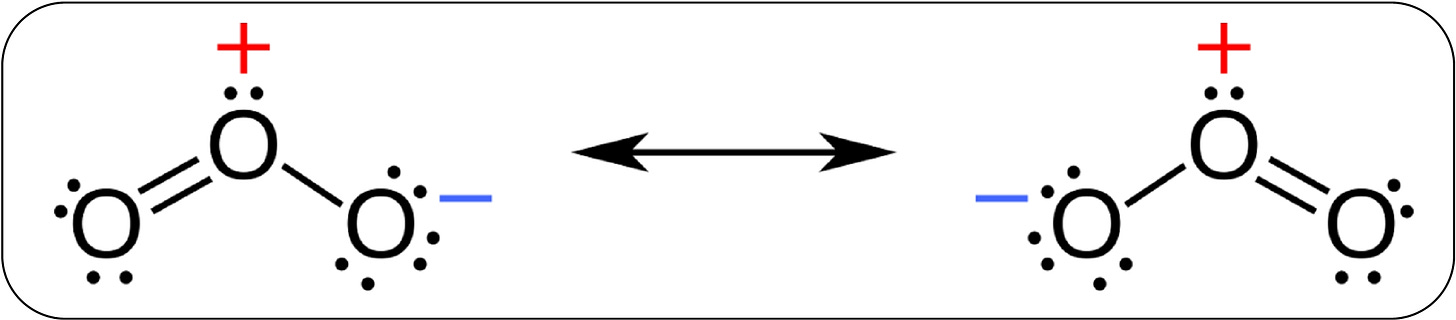

Ozone is a gas consisting of three oxygen atoms:

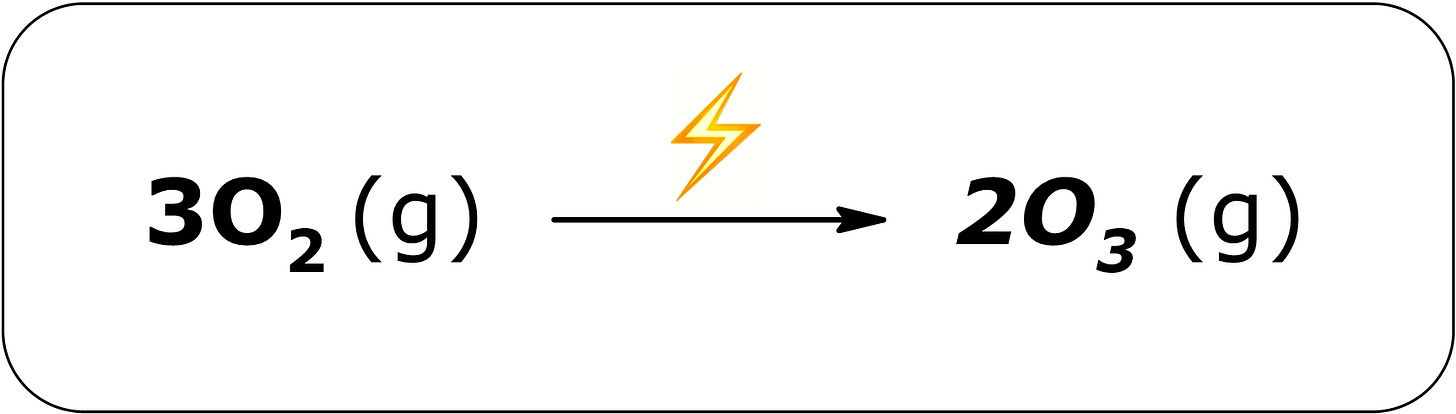

It has a sharp odor similar to chlorine bleach and readily reacts with organic materials such as latex, plastic, and living tissue. Ozone can be produced in thunderstorms when lightning splits oxygen molecules in the air:

In strong thunderstorms, enough ozone can be produced to smell. Ozone can be a harmful pollutant at higher concentrations, however. It can be formed above urban environments when various nitrogen oxides and organic compounds react under sunlight and heat. This can be a significant reason why air quality is lower during the summer months.

Why Rain’s Scent Triggers Nostalgia

The smell of petrichor is not just something that humans encounter on a rainy day. For many, the aroma of petrichor is a trigger for calm feelings and nostalgia.[15]

When one inhales petrichor, its components react with special receptors in the nose, mouth, and throat. This interaction creates a nerve signal that travels to the olfactory bulb, a kind of preliminary relay station for smell signals in the brain.[16] From there, the signals have a direct connection to the brain’s emotional processing and memory centers. Signals from other senses, such as touch or vision, follow a different route to the brain. To put it another way, smell is often strongly associated with memories because the nose has a direct pathway to the places where memories are stored!

Much like the smell of cut grass, petrichor may evoke nostalgia for the summer season, childhood, outdoor adventures, and hot days briefly interrupted by cooling rain showers.[15] For many, this association is positive, although it could be negative depending on how one feels about rain or thunderstorms. The perfume and cologne industries have attempted to capitalize on these associations with numerous products such as Demeter’s Rain and Miller Harris’s La Pluie.

One can find associations between memories and other aromas, as well. For example, inhaling cinnamon, ginger, and nutmeg makes many think immediately about autumn and the upcoming holiday season. Smelling flowers strongly reminds some of childhood or former lovers.[17] The power of perfumes, colognes, scented candles, wax melts, and potpourri is rooted in this connection between smell and memory.

The Chemistry Behind Summer’s Magic

The rain seems to stop almost as quickly as it started. The clouds, once so menacing and dark in the distance, begin to break up and allow beams of late afternoon sunlight through. Wet patches on the ground glisten in the sunshine. As the Sun’s heat returns, the rainwater turns to steam and seemingly vanishes. That distinctive, earthy smell fades away with it. The aroma may be gone, but the memory of it lives for much longer.

Summer is a season with a special kind of magic. Part of the magic of summer comes from the chemistry at work behind the scenes. The next time rain hits the ground, on a hot summer afternoon, give yourself a moment to take it all in. Enjoy the smell of the rain and the pleasant nostalgia for summers long gone. It’s a reminder that even the simplest moments can be shaped by science and chemistry.

References

Petrichor (Wikipedia)

Petrichor: The Smell of Rain (American Chemical Society Chem Club)

Geosmin (Wikipedia)

Paolina, G.; Avalos, M.; Olanova, D.; van Wezel, G.P.; Dickschat, J.P. Envrion,. Microbiol. 2023, 25(9), 1565-1574.

Podak, E.H.; Provasi, J. Chemical Senses, 1992, 17(1), 23-26.

Jüttner, F.; Watson, S. B. Appl. Environ. Microbiol., 2007, 73(14(, 4395-4406.

Rainfall Can Release Aerosols, Study Finds (Jennifer Chu, MIT News)

The Earth’s Perfume (Vivienne Baille-Garritsen, Protein SpotlightI)

Liao, Z.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Q.[ Khan, S.; Yu, X. Molecules, 2021, 26(16), 5939.

Ozone (Wikipedia)

Ozone Production from Lightning (Ozone Solutions)

What Memories Does the Smell of Fresh Rain Bring You? (Quora)